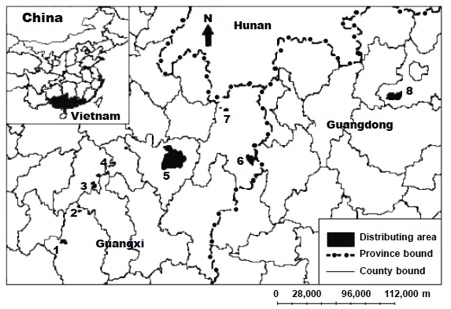

It’s been a very busy year, which explains why I am only now writing this blog post from my trip to China earlier this year (May-June). I had the amazing opportunity of seeing one of the world’s most endangered lizards—the crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus), in the wild, and working with one of the largest captive populations. Crocodile lizards are particularly unique because they are a monotypic family and genus (i.e., one species in the entire family). Sadly, this lizard has been heavily collected for the pet trade, particularly in Vietnam. It is endemic to a small part of Vietnam (slopes of Yen Tu Mountain) and southeast China (Guangxi Province). The Vietnam and China populations are separated by over 500 km. There are 8 extant (surviving) subpopulations in China and all are separated by at least 10 km. Five other populations are now thought to be extinct. Besides the pet trade, the other reason for their demise is a common theme—habitat destruction. And related to this, as forest is removed and people encroach on their habitat, their streams become polluted and uninhabitable.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus), in captivity.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus). In the wild.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus). In the wild, asleep at night.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus). In the wild.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus). In the wild.

- Crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus), in captivity.

This figure is from Huang, C. M., Yu, H., Wu, Z. J., Li, Y. B., Wei, F. W. & Gong, M. H., 2008. Population and conservation strategies for the Chinese crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus) in China. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 31.2: 63–70. “Fig. 1. Present distribution of the Chinese crocodile lizard (Shinisaurus crocodilurus) in China. Numbers indicate the eight areas of distribution: 1. D&B; 2. S&L; 3. LX; 4. GX; 5. JL; 6. DG; 7. LS; 8 LK. (For abbreviations see Method of survey in Material and methods.)”

I flew into Chengdu and met up with my regular collaborator, Dr. Qi Yin, from the Chengdu Institute of Biology (CIB), which is part of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. From there, we flew to Guilin, which is a popular tourist destination in Guangxi Province in part because of its spectacular karst topography. We were hosted by Professor Wu, who is head of the Department of Life Sciences at Guanxi Normal University, where we gave a talk to his research group.

After a few days in Guilin, we took the high-speed train, which travels at 200-250 km/h, from Guilin to Hexhou. From there, we drove about 50 km to the Hejiang River and then took a boat to the field station. I have to say that this was the first time I have worked in a reserve named after a lizard! We stayed at Guangxi Daguishan Crocodile Lizard National Nature Reserve, at an old forestry station.

On our first night, we ventured into the forest and walked up a stream where we saw 17 crocodile lizards, including a few babies from this year. Of course, the joys of working in rainforest is that you regularly get distracted by all the other cool fauna you find along the way. That night we also saw three species of snakes. One of these, Sinonatrix annularis (赤链华游蛇), is semi-aquatic and was common in puddles on the forestry roads where it dines on frogs. These snakes would quickly take flight at the first sign of danger, abandoning their shallow puddles in favour of dense vegetation. The other two snakes were a Pareas boulengeri (平鳞钝头蛇)and a Eurypholis major (翠青蛇), the latter was about 20 cm above Qi Yin’s head, tightly coiled in amongst some branches, staring nervously down at the top of his head!

- Hejiang River, start of boat trip to reserve.

- Entrace to Guangxi Daguishan Crocodile Lizard National Nature Reserve.

- He Mingxian at Guangxi Daguishan Crocodile Lizard National Nature Reserve.

- Enough said.

- Yin Qi and Luo Shuyi.

- Approaching the old forestry statsion where we would be staying at Guangxi Daguishan Crocodile Lizard National Nature Reserve.

- Unloading the boat!

- The team processing a lizard.

On a different night we sampled another stream, where we saw 23 Shinisaurus over about 3.5 hours. This was a narrower stream than the previous one, with some steep waterfalls (but not high) and fast flowing, clear water. We also saw a new agamid (Acanthosaura lepidogaster) sleeping on some vegetation near the water’s edge. And then, a real stroke of luck. While walking back along the road, we came across a krait (Bungarus multicinctus). This was the first time I had ever seen one, and it did not disappoint. It quickly went into defensive mode, and exhibited a range of defensive behaviour, including hiding its head.

While it was heartening that the streams with healthy populations of Shinisaurus still have clear water, it probably would not take much for that to change. And certainly, the nearby Hejiang River is badly polluted. Sadly, the local view is that the river is a convenient landfill—out of sight, out of mind. We did not see much aquatic bird life besides the occasional heron and a few kingfishers.

The captive breeding setup for the crocodile lizards is very impressive. The reserve has a large number of outdoor enclosures with circulating fresh water. Adults are generally kept in groups of four and babies grow up together in groups, but without any adults. When we arrived, there were some new pairings of lizards as part of a different study and we were able to observe a range of social interactions including some fighting and copulations.

Our work focused on behavioural interactions and the potential role of social behavior in any future release programs. To this end, we started with a simple experiment focusing on behavioural interactions between offspring and adults. There has been the occasional observation of adults eating babies, so were interested in whether babies could discriminate between their mothers and an unrelated adult female. We did not look at mechanisms of recognition, but merely whether they managed risk in relation to the identity of the adult with which they were presented. To examine this behavior, we constructed three Y-mazes in which babies could choose between associating with their mother vs no lizard (a stick), an unrelated adult female of the same size vs no lizard, or mother vs unrelated female. We are busy analyzing this data and don’t want to pre-empt the publication by giving away the findings. This information is potentially useful for future head-start programs when babies get released back into the wild.

We also spent several days measuring most of the captive lizards (148 in total), their bite force, and their spectral reflectance using an optic spectrometer. We also went into the forest to get irradiance measurements and background vegetation for calculating contrast. Male colour is variable and there appears to be several morphs depending on the preponderance of yellow or orange.

After wrapping up the Shinisaurus field work we had a day to do the tourist thing, and went on a boat trip down the famous Li Jiang River. This is a popular tourist destination and there is literally a long line of boats that proceeds down the river. The vista is spectacular—one karst rock formation after another, in a sea of hills. There is a point in the river that is illustrated on one of the Chinese bank notes and the thing to do is to hold up a bank note and photograph it against the background it depicts. We then left Guilin and flew to Haikou, a city on Hainan island, where we visited Dr. Wang, whose lab is working on a range of turtle and lizards. We saw his setup for freshwater turtles, as well as maybe about 10 or so marine turtles that are in rehabilitation.

- Acanthosaura lepidogaster, Guangxi Shinisaurus Reserve, China.

- Bungarus multicinctus, Guangxi Shinisaurus Reserve, China.

- Calotes versicolor, Hainan Island, China.

- Eurypholis major, Guangxi Shinisaurus Reserve, China

- Pyxidea mouhotii, captive, China.

- Polypedates megacephalus, Guilin, Guangxi Province, China.

- Pareas boulengeri, Guangxi Shinisaurus Reserve, China.

- Rhacophus dennysi, Guilin, Guangxi Province, China.

The purpose of this trip was to help Dr. Wang start a study on the Oriental garden lizard (Calotes versicolor). Unfortunately, we did not have much time, and the lizards were not as common as we thought. However, it turns out that they love hedges and there were more than a few hedges on campus so we concentrated our efforts there. These lizards are capable of dynamic colour change and go from a dull brown to a deep orange in less than a minute. They are truly spectacular in their orange and back display colour.

This was another great lizarding adventure in China. We certainly saw lots of cool herps and if you would like to see all the photos, check out our albums on Flickr.

An album of all photos from the China field work.

An album of Crocodile Lizard photos and portraits.

An album of lizards from China.

An album of snakes from China.